The first governor of the Canary Islands ordered the construction of a tower at the end of the fifteenth century, and when it was extended a few years later, the space located between the tower and the new perimeter walls was filled with earth to increase the building’s strength and resistance. That purely defensive need would become the structuring argument of our architectural proposal for the Castillo de La Luz. Located in La Isleta, the isthmus at which the Castilian ships protecting the city arrived, it concealed those primitive walls originally beaten by the sea. The passage of time affected not only its initial use and preservation, but also the conditions of its closest environment: the old coastal fortress that was wrapped by the water during high tide became gradually surrounded by the structures of the port and the growing city of Las Palmas. After being involved in battles at the end of the sixteenth century—in which the city was plundered, burnt, and rebuilt—the fortress retained its military role but gradually declined, reaching the twentieth century in a state of ruin. In the 1960s, however, it was partially reconstructed to become an exhibition gallery.

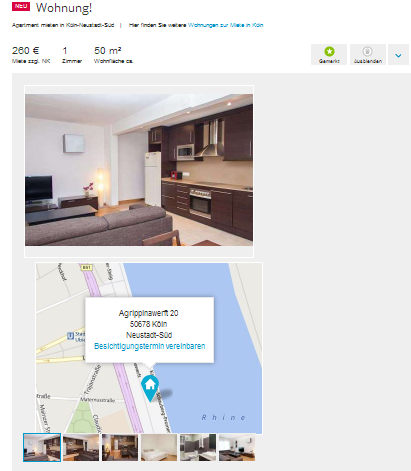

When undertaking the project to build in the historic castle, which was to be transformed into a new exhibition space equipped with the installations appropriate to a contemporary museum, we decided to begin with a close reading of the circumstances of its past. If, for five centuries, the space between the outer walls and the original tower had remained hidden, filled with earth, our task essentially consisted in emptying it and recovering the view of the primitive fortress, transformed now into the protagonist of the new museum. Where once there was only hardpan, a space up to now concealed from view, a void emerged, covered with a white concrete slab that is separated from the stone walls of the old tower to let natural light pass through narrow skylights. On the exterior, a recently built, fake perimeter pit has been dismantled to free up a vast surface of the terrain on the original, ground level of the fortress, revealing its full dimensions. A new, partially buried pavilion adds complementary spaces for the museum: access, shop, restrooms, storage, and multipurpose hall. A thin horizontal platform that barely emerges from the terrain will be the only visible trace of an intervention that aims at going unnoticed adjacent to the building it serves and complements.

Any contemporary intervention in historical heritage generates a difficult relationship. On occasions like this one it becomes the expression of a direct and clear response to the apparently insignificant circumstances, which simply demanded one fundamental action. Rather than rebuilding or renovating the Castillo de La Luz (“castle of light”), we merely emptied it, revealing its concealed past, now transformed into a space filled with light—as if paying tribute to its name—by means of an architecture that displays itself and its own history.

↧